Webb visits a stellar nursery

An in-depth look at the largest star-forming region on the Milky Way

As mentioned in previous articles, clouds of gas and dust, nebulae, are the places where new stars are formed. In galaxies such as our own, the Milky Way, they are scattered throughout the spiral arms of its flattened-disk body. Imagine, if you would, a large, round flat lid from a large container. Add small tufts of cotton wool scattered along spiral lines coming from the center of the lid’s surface; each one of these represents such star-forming clouds.

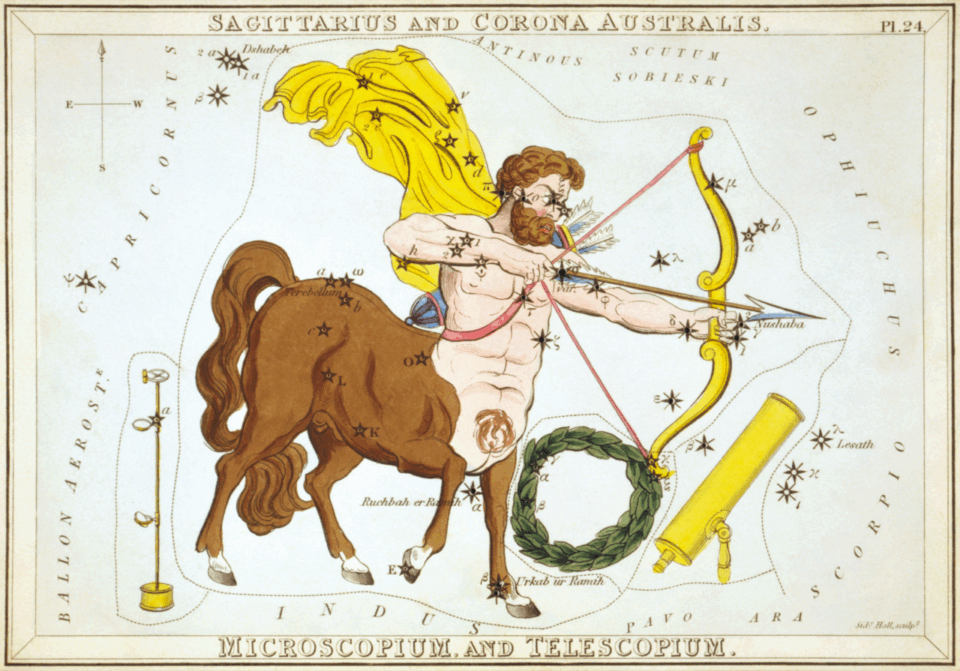

All disks must have a center, and for our Galaxy it happens to lie in the direction of the constellation of Sagittarius, the Archer, one of the well-known summer constellations, though here in Sweden it’s fairly close to the horizon and doesn’t get up very high above it. When you follow the ghostly band of the naked eye Milky Way across the late summer-early autumn sky toward the south (after Swedish nights get dark again), that’s where it’s located.

Not only is this the center, but it’s also where the greatest concentrated amount of such material in the Galaxy is located. Sweeping even an amateur-sized telescope across this part of the sky as seen in this picture reveals large numbers of colorful nebulae and bright star clusters, which are the end result of nebulae turning into such objects.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has turned its powerful eye on the largest known cloud of nebular material in the Milky Way, Sagittarius B2, also known as Sgr B2 for brevity. There it has found large numbers of hot massive stars as well as huge clouds of glowing gas excited by the ultraviolet energy the stars give off.

Sgr B2 lies only 390 lightyears from the center of the disk, which also places it that far away from the supermassive black hole at the Galaxy’s heart called Sagittarius A* (pronounced “Sagittarius A Star”), a region densely packed with stars, star-forming clouds, and complex magnetic fields. We’re no exception when it comes to such black holes as most of the spiral- and elliptically-shaped galaxies astronomers look at also have these powerful objects located in their centers; some are much larger than others.

When we speak about the center of our Milky Way keep two things in mind; it’s about 100,000 light years in diameter; from one side to the other. Our Sun lies about 26,000 light years from the middle itself, placing us in one of its spiral arms

In this JWST image, taken with its NIRCam instrument in the near-infrared part of the spectrum, we can see dozens of very bright massive young stars, complete with long spikes around them, artifacts caused by Webb’s optical system. The pinkish-orange clouds are star-forming nebulae, molecular clouds of gas and dust made to glow by these stars. Basically, they are acting like giant gas-discharge tubes we see on the outside of buildings in colorful lighting displays. But rather than, for example, using neon gas, these contain hydrogen, which glows this color when excited by ultraviolet light’s high energy. The dark patches seen within these clouds is not empty space, but where it is so dense with material that light coming from behind cannot pass through them.

This view of the same area was made with Webb’s MIRI detector, which “sees” in the mid-infrared part of the spectrum, and look at the difference in the results. For one thing, there are fewer massive new stars seen now because at this wavelength the gas and dust appears much denser, with only the brightest and most powerful showing up as small blue points of light. It’s the nebulae themselves, however, which show the greatest difference. This UV-warmed gas shows up much more strongly now. Once again the dark features in the nebulae are areas too dense for light to pass through.

If you look carefully there is something else revealed. Ionized hydrogen gas , an emission nebula, glows in red tones, but when its reflecting light and not glowing, it shows up as blue; what’s known as a reflection nebula. Look carefully at this MIRI image and see if you can spot the areas where there is evidence of these ghostly-blue reflections.

In this montage image I made combining both of Webb’s views, you can get some idea of how much the mid-infrared view hides many of the stars seen in the one in near-infrared.

Studying Sgr B2 will help astronomers understand how star formation can take place under the unusual conditions of being so close to Sagittarius A*, the powerful giant black hole at the center of Milky Way.

For the official JWST press release and a very interesting, real-time comparative look at the two different views of Sagittarius B2, follow this link.

By: Tom Callen