Jackstraws in the sky

Satellite trails pose an increasing threat to ground-based astronomy

Back in June 2023, I wrote an ESERO Sweden news article about astronomer’s efforts to get rid of the lines caused by satellites passing through the view of the Hubble Space Telescope when it was taking pictures of astronomical objects. This example shows one such interloper “photobombing” a pair of distant interacting galaxies, which are exchanging a stream of faint material between themselves.

As you may already suspect, there are even more satellites orbing our planet now than there were from my reporting over two years ago. Not only do these lines ruin photos taken by large research observatories, but they can also affect those who do so as civilian scientists through the long-standing hobby of amateur astronomy.

A long-term astronomical friend of mine in the States recently sent me a pair of photographs taken by another member of the local astronomy club he belongs to in Rochester, New York; the city where I grew up. Captured using more advanced techniques than the average amateur, I was very impressed by Burney Baron’s two images. They are also great examples of what can be done today with equipment available to those who want to try doing so themselves.

Back in October, there was a celestial visitor to the inner solar system crossing the northern part of the night sky; Comet Lemmon (a.k.a. C/2025 A6). Discovered in early January of this year, it took about 1,350 years to travel inwards from the outer reaches of the solar system on its very eccentric orbit. The last time it had passed so close to the Sun was sometime in the second half of the 7th century C.E.

Traveling the roughly 70 km southeast from Rochester to the swimming beach at Keuka Lake State Park, Baron captured this view of Comet Lemmon. Using a 17mm focal length wide-angle lens on his digital single-lens reflex camera, it shows how it appeared to the naked eye. This also brings up the point that astronomers often have to travel in order to find some good dark skies to make their observations.

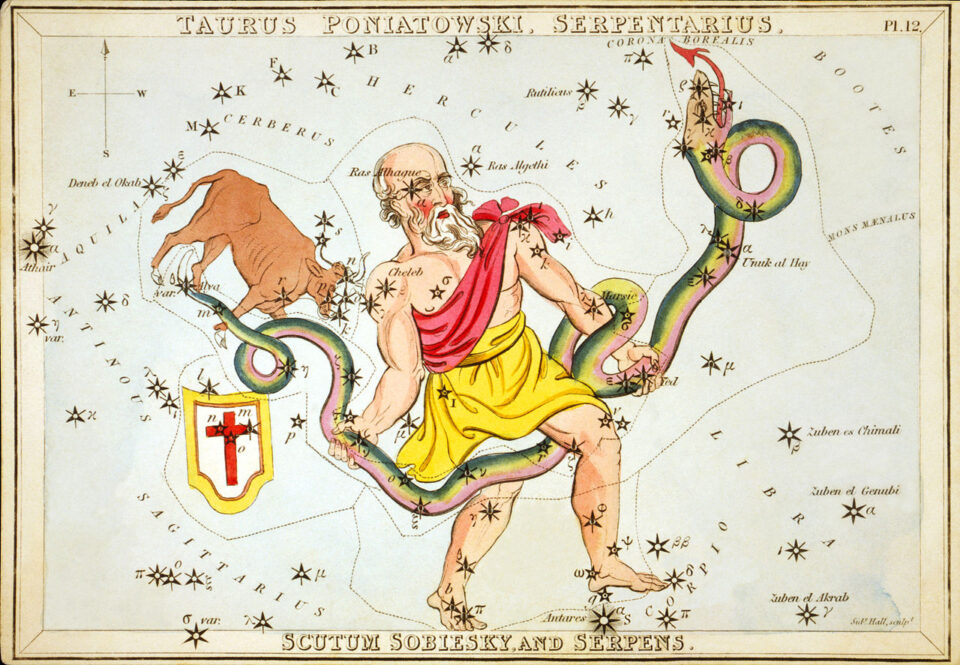

At the time it was photographed, Comet Lemmon was seen against the stars of the constellation of Serpens, the Snake, or more specifically, Serpens Caput, the Snake’s Tail. Serpens what?

If you’ve never heard of this group, you’re not alone. At one point in time, the constellation of Ophiuchus, the Snake Bearer, included the large snake he’s seen holding. Later on, the snake became a constellation in its own right, but because Ophiuchus was still in the middle, it was split into two halves; Serpens Cauda (the snake’s head) and Serpens Caput (the tail). So, at the time when Baron took the photo, it was in the tail-end part of the snake.

What I really want to emphasize here are the following two photographs which had originally been sent to me. A couple of earlier articles this year have mentioned the digital photographic technique where individual pictures of the same object can be “stacked” on top of one another using special software to build the best image possible.

Referring back to stacking again, they were made by taking 77 images, each with a duration of 25-seconds. The camera was using a light sensitivity setting (i.e., ISO) of 1,600—good for capturing faint objects—and a 135mm lens, which is a medium-power telephoto lens. Such image magnification would also exaggerate Earth’s eastward rotation, making the images of stars streaky and the comet blurred. To compensate for this, Baron used a simple tracking device popular with amateur astronomers. Motorized to move in the opposite, westward direction and at the same speed as our planet’s rotation, the two motions cancel each other out, leaving pinpoint stars and a beautiful comet captured.

In this magnified view of Comet Lemmon we can see its bright head, or coma, at the front end and its long tail streaming away behind it. If you look carefully, you can actually make out two tails. There is the bluish-white plasma tail pushed back by the solar wind coming from the Sun, but there’s also the yellowish dust tail curving away to the right. Why is that?

A comet’s dust tail does not exactly follow its nucleus hidden inside the coma due to two effects: solar radiation pressure, plus this frozen ball of gas and dust’s orbital momentum. These heavier dust particles leaving the comet’s head lag behind, forming the curved tail. This dust, which is relatively more massive than the gas particles in the bluish-white ion tail, isn’t affected as much by the solar wind, but more by its own inertia.

Notice anything else about this photo? All of those yellowish, jackstraw-like streaks cutting across it are satellites in Earth orbit. These were all captured in the total half-hour used to take the 77 pictures stacked together into the final portrait of Comet Lemmon. Not only that, but they are mostly all part of what’s known as a single “satellite constellation”.

Perhaps you’ve heard of the Starlink system of satellites, operated by Elon Musk’s SpaceX, which are used to spread the Internet to places around the world where it’s not easy to access it. Rather than having, for example, fiber optic lines to route it, you can actually use small portable antennas to wirelessly connect to the Internet no matter where you are. Ukrainian soldiers use it extensively in the fight against their Russian invaders.

Back in 2023 there were roughly 4,500 of these mass-produced satellites orbiting Earth; today, there are around 8,811, or almost double the amount in two years.

Starlink trails account for all of those which are going from the upper left to the lower right of this picture. The others crossing them at almost right angles are other satellites not a part of SpaceX’s Internet constellation, at least one spent rocket booster, and some random commercial passenger aircraft thrown in for good measure. No matter who launched them into orbit, they’re clearly nothing we want to look at. Recall that this is the same sort of problem large observatories, like the Hubble Space Telescope, also have.

Fortunately, the image processing software used to combine the pictures into the final one is also capable of subtracting all the “jackstraws” caused by Starlink and the other sources. Considering these lines to be data not consistent between the individual picture frames they’re removed via an algorithm, with the end result this beautiful image of Comet Lemmon traveling towards perihelion. its closest passage to the Sun. You can also now better make out both the ion and dust tails too.

I’ll leave you with this final composite image I made, which compares the two views of Comet Lemmon; with and without satellite trails. If you’re like me, I’m sure you prefer the half without the “jackstraws,” but, unfortunately, the situation is bound to only get worse over time.

The total Starlink network is expected to reach up to a total of 42,000 satellites(!), but there is at yet no date when it will be completed. So far, SpaceX has received permission for an additional 12,000, and they’ve also filed the paperwork for 30,000 more. The final number of those launched will be determined based on future demand.

The European Space Agency (ESA), of which Sweden is a member, is playing its part in trying to lesson the amount of space debris circling our planet, like old satellites, through a variety of initiatives. You can read more about those here.

By: Tom Callen