The Moon and media

Astro-news you can use

No matter where you get your news from these days, whether it be from mainstream media, social media, even places like legacy newspapers, we hear of references to astronomical events. Unfortunately, they don’t always come with the best, or any, explanations as to what they’re referring to.

To help you and your students better understand one of the most common objects referred to, the Moon, I’ve included here three of the most commonly types used in a “deep dive” on the subject.

Part 1: What Moon is it?

You may have already noticed that in at least the last five or more years mainstream news articles refer to a month’s Full Moon phase by a particular name, such as the “Beaver Full Moon” used this past November. What exactly do these mean, and is there really anything to them?

First and foremost, let me just say up front that these names carry no recognition as being official, but have been used to attract attention to the story about the event itself. There is a Full Moon every month, and if you tag it somehow, it gets “more interesting.” Again, while they have no official sanctioning, but do encourage people to go out and look at the night sky, then perhaps they aren’t so bad after all.

Two more recent examples come to mind for September and October; the Harvest and Hunter’s Full Moons. Both of these are tied to their useful practicality as the Harvest Moon makes a lower path across the September night sky, making it easier for farmers to get in some more time for gathering autumn crops. October’s Hunter’s Moon is similar, though in this case it allows hunters some more moonlight in order to help fill their larders for the coming winter months.

In this view we can see a good example of the Harvest Moon, its orange color due to the fact that our satellite’s orbit makes it take a low path across the night sky this time of year, As a result, many more of the blue rays from its reflected light from our Sun get scattered away by Earth’s atmosphere, an effect called Rayleigh Scattering, leaving those colors mostly at the red end of the spectrum.

Where do these names come from? A lot of them used in North America and, by extension, in other places of the world, came from Native American tribes, which could be used to relate to something during the month in question. For example, November’s Beaver Moon was when they noticed that these aquatic mammals were starting to get their mound-like homes made out of sticks, known as lodges, ready for the winter. These were later picked up and used by what’s called the Farmer’s Almanac, which was a useful aid to farmers in the form of an annual calendar.

The complete listing for the year is as follows:

| Month | Full Moon name | Refers to |

|---|---|---|

| January | Wolf Moon | Hungry wolves howling for food |

| February | Snow Moon | Named for cold, snowy weather |

| March | Worm Moon | Trails of worms begin to appear in newly thawed ground |

| April | Pink Moon | Named for the early blooming of certain wild flowers |

| May | Flower Moon | Named after the majority of other flowering plants blooming |

| June | Strawberry Moon | The start of the time to gather strawberries |

| July | Buck Moon | Male deer, who have shed their antlers earlier in the year, begin to grow new ones |

| August | Sturgeon Moon | Abundant catches of this large fish takes place |

| September | Corn/Harvest Moon | Named for the gathering of crops grow over the summer |

| October | Hunter’s Moon | A good month to hunt wild game, such as deer, by moonlight |

| November | Beaver Moon | When the beavers prepare for wintertime |

| December | Cold Moon | The coming of dark cold months with the Winter Solstice |

Coming closer to home, what about here in Sweden? As it turns out, the indigenous Sámi people who live in the far north of Sweden, Norway and Finland have some traditional names for monthly Full Moons, which are also often based on the characteristics of events throughout the year in their homeland of Sápmi.

Their culture is intrinsically linked to the natural world and reindeer herding, so some of the months are named for what’s going on in their all-important reindeer migration cycle. Here is one listing of Sámi months I found. Note that each contains the element “mánnu” at the end; the word for “month,” or “moon”:

| Western month | Sámi month | Refers to |

|---|---|---|

| January | Ođđajagemánnu | New Year Month |

| February | Guovvamánnu | Unknown/uncertain etymology |

| March | Njukčamánnu | Swan Month (when the swans return) |

| April | Cuoŋománnu | Snow Crust Month (when the snow has a hard crust in the mornings) |

| May | Miessemánnu | Reindeer Calf Month (when calves are born) |

| June | Geassemánnu | Summer Month |

| July | Suiodnemánnu | Hay Month (haymaking season) |

| August | Borgemánnu | Molt Month (when reindeer shed their coats) |

| September | Čakčamánnu | Fall/Autumn Month |

| October | Golggotmánnu | Rut Month (reindeer rutting season) |

| November | Skábmamánnu | Dark-Period Month (around the winter solstice) |

| December | Juovlamánnu | Yule Month (Christmas season) |

Just to finish up on naming Full Moons, from what I found on the Internet there aren’t any widely recognized, specifically Swedish month names for every Full Moon. While the concept of naming them is present in some Nordic tradition, they’re often tied to mythology or seasonal events. Like other cultures, people in this country would have historically tracked time using the approximately 30-day lunar cycle, linking moons to important events, like crop harvests and winters.

The specific Full Moon names commonly used today, like the ”Wolf Moon” or ”Flower Moon,” are primarily of North American origin, which have also been adopted in other parts of the world. Some former Northern European pagan and folk traditions, which have influenced Swedish culture, have had their own names for specific Full Moons. For example, the ”Yule Moon” was associated with the midwinter festival of Yule, which is celebrated in Scandinavian countries.

Part 2: Perhaps not as creepy as it sounds

Different monthly names used by mainstream and social media to refer to the Full Moon, such as November’s Beaver Full Moon, are one thing, but we’re not done just yet. Perhaps you’ve also seen reference to something called the “Blood Full Moon.”

If this one sounds confusing, unusual, even creepy, you’re not alone in thinking so. And, truth be told, like the various names for the Full Moons seen throughout the calendar year, this is being used by the mainstream media to make a naturally-occurring astronomical phenomena sound “newsworthy.” Don’t get me wrong into thinking that news outlets are trying to trick you; it’s just that they want to get your attention. Up until five-years-ago or more, you never heard them referred to, though even nowadays NASA has given in to using them too.

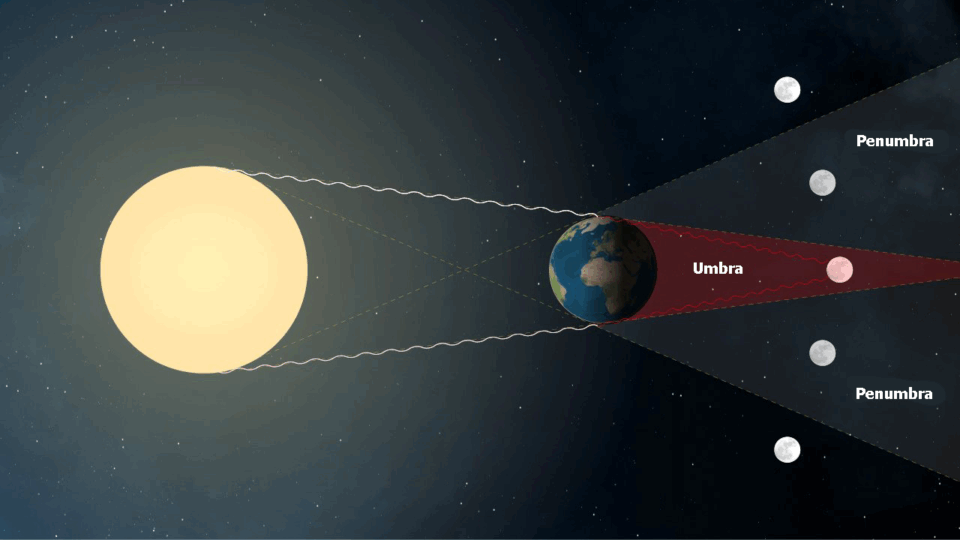

The name “Blood Full Moon” is really nothing more than an ear-catching name for a total lunar eclipse. These events, when our satellite passes through Earth’s shadow while traveling along its orbit, happen about one every other year, though there can be none, one, or two. It all depends on the relationship between the Moon’s position and the projection of our planet’s shadow out into space.

So where does the “blood” part come in? This actually refers to the color the Moon can become while in the densest part, the umbra, of the shadow. There are actually two parts to such a shadow:

- Penumbra – the lighter outer shadow

- Umbra – the darker inner shadow

This diagram – which is not to scale – shows the relationship between the Sun, Earth, and Moon during a total lunar eclipse. You can see the darker, reddish umbra part of the Earth’s shadow projected onto the Moon surrounded on the outside by the light gray penumbra.

These colors seen during a total lunar eclipses depending on the amount and type of particulates in Earth’s atmosphere – dust, pollen, smoke, volcanic ash, very fine sand, etc. – as well as how much of our planet’s shadow the Moon passes through. What sort of colors can you expect to see? Penumbral colors tend from almost being invisible to light grays, while umbral colors can be yellow, yellow orange, orange-red, brick red, dark red, dark blue-gray, to almost being invisible as a dark gray.

In a personal example, I remember seeing a very dark gray total lunar eclipse back in the 1980s, which gave the appearance there was a hole in the sky surrounded by the rest of the starfield. While I could barely see the totally-eclipsed Moon naked eye, I could see its very dark-disk with binoculars, including some large, barely illuminated craters. Why doesn’t our eclipsed satellite completely disappear? Because of Earth’s atmosphere. The Sun’s light gets refracted around the edge of our planet, so, if we had no atmosphere at all, the Moon would be completely black every total lunar eclipse.

The Danjon scale

An astronomer at the Paris Observatory, André-Louise Danjon (1890 – 1967), came up with a color scale to help describe the different colors the totally-eclipsed Full Moon can appear. Known as the “Danjon scale,” it consists of five levels.

| L value | Description |

|---|---|

| L0 | Very dark eclipse. Moon is almost invisible, especially when in the deepest part of the shadow |

| L1 | Dark eclipse, grey or brownish in color. Details on the lunar surface are distinguishable only with difficulty |

| L2 | Deep red or rust-colored eclipse. Very dark central shadow on the Moon’s disk, while outer edge of umbra is brighter in comparison |

| L3 | Brick-red eclipse. Umbral shadow usually has a bright or yellow-colored rim |

| L4 | Very bright, copper-red or orange coloring. Umbral shadow has a very bright, bluish rim |

Look at this beautiful image of a total lunar eclipse taken in California on the evening of 15 May 2022. Again, the reddish color is being produced by sunlight being refracted by Earth’s atmosphere, which gives it this color. Note that it’s darker at the top edge of the Moon than at the lower one, so the shadow it’s passing through is denser where it’s darkest.

In conclusion, you have a much better chance of seeing a total lunar eclipse than a total solar eclipse. The former can be seen by whole hemispheres on planet Earth for up to a few hours in duration. The latter can only be viewed from a very small area on Earth’s surface, but only for a maximum of up to about 7½ minutes. And, in order to see such an event featuring the Sun, you are guaranteed to have to travel someplace in order to see it: a tourist industry all of its own. On the other hand, you won’t be alone as thousands of people do it every year there is a total solar eclipse.

Part 3: Maybe not so ”super” after all?

The two previous types of names for the Moon as used by mainstream-and social media referred to each month’s Full Moon and total lunar eclipses, both which are events that are pretty obvious in and of themselves.

A Full Moon is pretty hard to miss (the former), and one which has turned a very conspicuous red color even more so (the latter). These next names used for lunar events as described here are far more subtle to the point the average person won’t even know they are happening without being actually told they are in progress, yet there can be mention of them in the news media.

The Moon-related names discussed here are the “Super Moon,” and another called the “Mini Moon” or “Micro Moon.” I’m reasonably sure you’ve heard the first one, but the other one—in either of its two variations—is perhaps not mentioned as often. It too, though, is something naturally occurring.

As you already know, the Moon orbits our Earth. Like most of these for objects in the solar system, regardless of their size, it’s not a perfectly round circle, but is elliptical in varying amounts depending on the planet, their satellites, etc. Not only that, but Earth doesn’t lie right in the exact center of the Moon’s orbit either. The end result is that part of the Moon’s orbit is farther from (apogee) and another closer to (perigee) our planet.

If these last two orbital terms sound a little familiar, you may have heard them in another guise: perihelion and aphelion. The prefixes “peri” and “ap or apo” come from ancient Greek, with the first meaning “near” and the second “away from.” The “helion” half refers to the Sun, after the god Helios So, to define these, they mean “near the Sun” and “away from the Sun.”

With perigee and apogee, the “gee” part (think “geo”) denotes planet Earth; both closer, the former, and farther, the latter. I’ll leave it to you as an exercise to try and figure out what the terms perilune and apolune mean; they are also sometimes referred to as periselene and aposelene. Here’s a hint: they have something to do with the solar system body the subject of this article is about, and artificial things, like spacecraft, orbiting it.

When it comes to the Moon orbiting Earth, at its farthest distance (apogee), our natural satellite is 405,507 km away, but when closest to us, it’s at 363,300 km. The difference between these two extremes is 11.6%. To put these in terms of the Super Moon and Mini/Micro Moon, we see the former at perigee, when nearer, and the latter at apogee, when farther.

This photo of Earth’s closest companion in space was taken when it was a Super Moon on 8 March 2020. If, however, I hadn’t told you it was so, would you have noticed the difference? Even if the same picture contained foreground objects, like Earth’s horizon, for comparison purposes, you’d still find it difficult to see it being super; i.e., larger, than normal. While the Moon is not quite 7% larger when it’s a Super Moon as compared to a normal Full Moon, without the proper kind of measuring equipment, you as a naked eye observer would be unable to tell the difference.

Not only does this apply to its disk’s apparent angular diameter, but also its brightness, which also varies somewhat depending on if it’s a little farther from, or a little closer to us. In the case of a Super Moon, it’s around 16% brighter. Part of the problem with determining brightness naked eye is the fact that the Moon is so bright it dazzles your eyes. It is, after all, the second brightest thing in the sky after the Sun. Another problem determining brightness is because there is nothing else in the sky to compare it with outside of a dark, star-filled background surrounding it.

Following the example of Super Moons, what about Mini/Micro Moons as compared to the regular Full Moon? It’s about 7% smaller, and roughly 15% less bright.

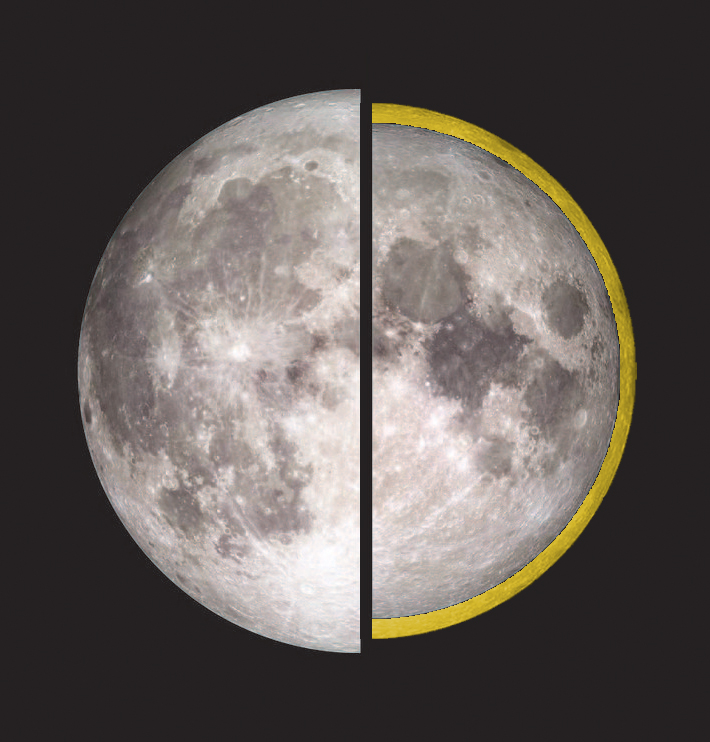

If you were to do the same comparison between the smaller Mini/Micro Moon and the larger, Super, Moon, the latter comes out to be a little over 14% larger and some 30% brighter. This is what’s being shown in this composite picture of the Moon I made. Taken at two completely different times by NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. One side is of a Super Moon (left half), compared to a Mini/Micro Moon (right half).

If you stretch your imagination a bit, you can mentally place the regular Full Moon in between the two (the yellow disk I added), filling up the small difference between the top and bottom of the two halves. As you can see, without anything to serve as a base of reference to compare between one or the other to the Full Moon, it’s very hard to see a difference whether it be larger or smaller.

One could see that out of all the unofficial names applied to the Full Moon, those here are the ones with the least amount of significance. If you can’t actually tell it’s different—larger, or smaller—what’s the point? They do, however, get people outside and looking in hopes of seeing something unique when it’s reported by the media.

Perhaps the best approach is to take the I one I do. Enjoy the Moon when you’re outside observing no matter what its phase, whether or not it’s eclipsed, or whatever distance it is from Earth. And you’re not alone in doing so. It’s something we humans have been doing for hundreds of thousands of years without even having to give our closest neighbor in space a name of any kind.

Post script

The same night I was finishing this deep-dive up, yet another Moon name came to mind as I was going to bed. And it’s one which is used even less than any of the others already mentioned. While one of them, like “Super Blood Moon” (a total lunar eclipse when the Moon is closest to Earth at perigee) sounds almost threatening, “Blue Moon” does not. One could say it’s almost calm and relaxing in comparison.

What’s a Blue Moon? No, Earth’s natural satellite doesn’t physically turn blue-looking in color. It’s when there are two Full Moons happening within the same calendar month, which, if you think about it would be pretty unusual. It’s also where the colloquial expression, “Once in a blue moon” comes from just because they’re so rare.

The Moon’s normal cycle of phases—New to First Quarter to Full to Last Quarter and back again to New—takes 29.5 days, which means that February with only 28-days can never have two Full Moons in it. This even would include 29-day leap years. So, in any month with 30- or 31-days it’s possible to have one Full Moon at the very beginning, and then a second one 29.5 days later; before the last day of that month.

Mark your calendars: the next time there’ll be a Blue Moon will be on 31 May 2026, with Full Moons on both the 1st and 31st of that month!

By: Tom Callen