The Sun hits its maximum

Our star reaches the peak of its 11-year cycle of minimum-maximum solar activity

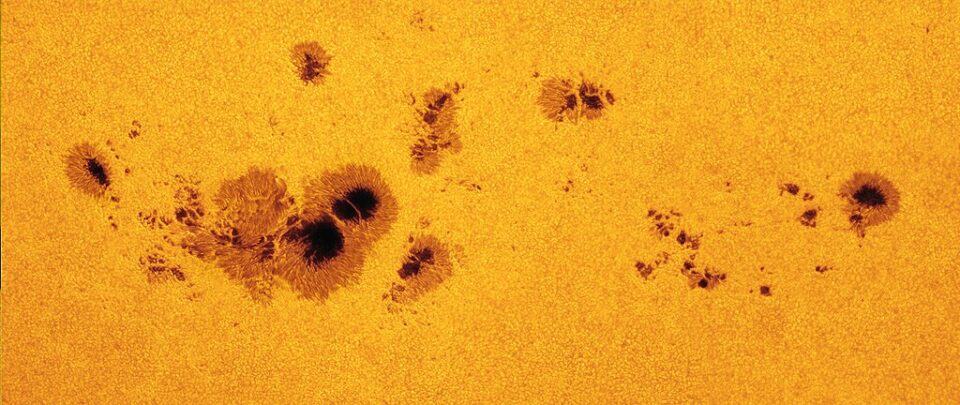

To us here on Earth, our Sun appears to be a constant, never-changing source of light and heat, “rising” every morning and “setting” every evening due to our planet’s rotation. If you were to examine its surface on a regular basis you would start to notice at least one easily-seen feature. These dark marks, called sunspots, appear singly or in groups against the lighter background. Temporary in nature, they can last for days or months before fading from view.

Being cooler than the surface of our star is what makes them become contrasty, though they are still 3,000° – 4,200°C as compared to the Sun’s surface temperature of around 5,700°C.

This image of a sunspot group was taken by amateur astronomer Alan Friedman in July 2012. The largest spot to the left stretches to more than 11-times the diameter of Earth, or just over 140,000 kilometers across. The full chain of spots, left-to-right is closer to being 322,000 km across.

When the Sun is at its sunspot minimum, its magnetic field behaves like a conventional bar magnet with two distinct poles: north and south. But as it continues towards maximum, the field becomes more complex and tangled as the poles completely flip direction; south becomes north and vice-versa. In this comparison from NASA, we can see the almost sunspot-free solar surface at minimum versus the spotted one seen toward the end of the 11-year cycle.

Such disturbances in the surface of the Sun are caused by these complex changes in its magnetic field during a solar cycle. This short timelapse video, made by another amateur astronomer using a 20 cm telescope with a very special kind of solar filter looking at an extremely narrow part of the electromagnetic spectrum: a wavelength called hydrogen-alpha. Allowing safe views of our star, it shows activity around a sunspot as affected by such fields.

Solar cycles, starting with number 1, were begun to be tracked from February 1755. This doesn’t mean that the Sun began to display this behavior then, but the Sun’s cyclical sunspot pattern was not recognized until 1843. An examination of the historical observational records of sunspot counts, beginning as early as 1610 following the invention of the optical telescope in1609, narrowed its length down to just over 11-years. Unfortunately, such data was spotty prior to 1755 for complete cycles to be identified, so this is why solar cycles are counted from then.

Solar cycle 25, which started in December 2019, was predicted to hit its maximum sometime between October 2025 and January 2026. And the international astronomical body keeping track of the sunspot count leading to the determination of reaching that maximum has said it was in October. During that period of time the number of sunspots at the start of cycle 25 went from a minimum average of 1.8 per day to 161 by the time of the October maximum.

Greater sunspot activity on the Sun means the more the chance there are increased streams of energetic particles erupting from its surface heading toward Earth, causing the aurora borealis. Attracted to our planet’s magnetic field, these particles lend a little extra energy to the atoms in the gases, like oxygen and nitrogen, making up Earth’s atmosphere. This energy causes the outermost electron of these atoms to temporarily leave them, but it doesn’t do so for long. In order to rejoin their atoms again, these stray electrons must give off the energy, which made them escape to begin with. It’s does so in the form of emitting a little burst of light, which is what we see as the aurora borealis.

There have been a number of large displays in the last few weeks where displays were seen even at latitudes much farther south than usual, such as Florida in the United States. Unfortunately, at least here in the Stockholm area, we’ve had cloudy weather for most of this period with only a couple of clear nights. But we noticed no displays under the relatively dark skies where we live out in the Stockholm Archipelago.

Fortunately, the night sky was clear up in Dalarna for ESERO Sweden Ambassador, Jenny Jansson, who was able to capture this beautiful view of the aurora. It even includes the asterism known as the Big Dipper: a part of Ursa Major, the Big Bear. Based on the left-to-right, ripple-like structure seen in the display, we could call this a curtain-type aurora.

Keep an eye out for clear nights, preferably free of the bright Moon, during the weeks ahead. There can still be plenty of opportunities to see the aurora borealis, providing the Sun sends us the energetic particles we need for them to be caused in the atmosphere. Just because there is such an eruption on the surface of our star doesn’t mean we’ll see anything; they have to be aimed toward Earth, and they could fly off in any direction from the Sun.

By: Tom Callen