Christmas Eve 2025

Continuing the seasonal tradition

Believe it or not, it’s now time for ESERO Sweden’s 100th article about space and astronomy on our news page. We’re highlighting this with an article for children and adults, focusing on this year’s starry sky on Christmas Eve.

In what so far is a mild December, and as done in previous years, here’s an activity for the whole family for Christmas Eve: go outside and share the current night sky together. These maps are current for this year, but if the weather isn’t clear where you live now, you can use the same maps for a couple of weeks into January. Remember then that you need to look earlier and earlier each evening for the starry sky to match the map.

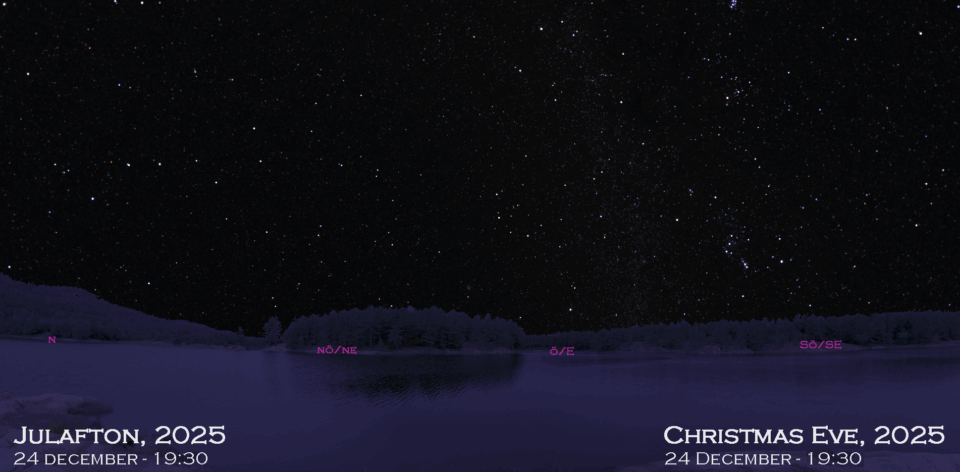

Stepping outside, try to find a dark place with an unobstructed view of the night sky, and allow yourself some time to get dark adapted if you can. The more you do, the more you’ll see. As shown here, the view extends from north (to the map’s left) all the way to southeast (at the right). Note the letters indicating the cardinal points of north, northeast, east, and southeast along the horizon. The time of night is 19:30, so it shouldn’t be too late for even the younger members of the family. Both the directions and time are the same for the all the other maps to follow. Looking around, particularly to the east and southeast you should see some bright stars scattered across the sky.

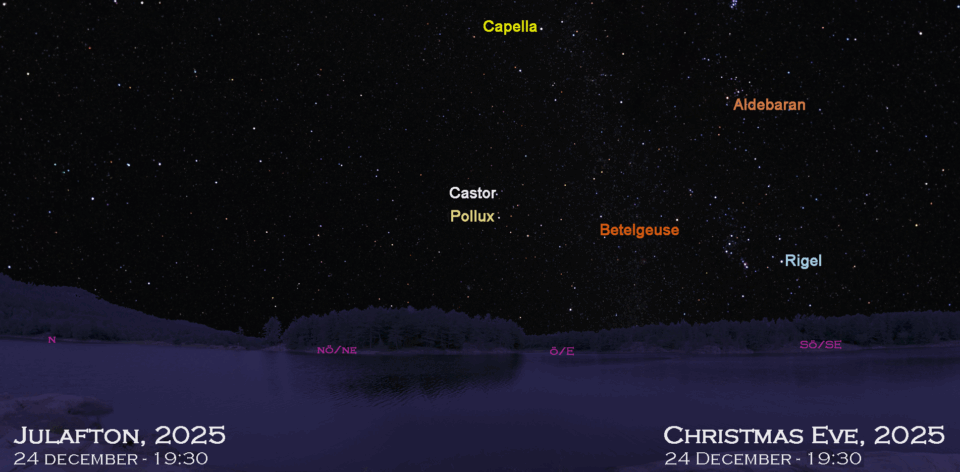

The winter sky contains both some of the brightest stars of the night sky, but also some of the most colorful. In fact, there are 11 naked eye stars which readily show apparent color, and six of them are named here. I’ve tried to color their names in approximations of their colors, which is an indication of their temperature. Redder stars are cooler, yellow stars medium hot, and white and blue-white the hottest. You might have to be in a pretty dark location to make these colors out, but they do exist. Let’s list them all out along with the star’s names: Castor (white), Pollux (light yellow), Capella (golden yellow), Aldebaran (orange-red), Rigel (blue-white), and Betelgeuse (red-orange).

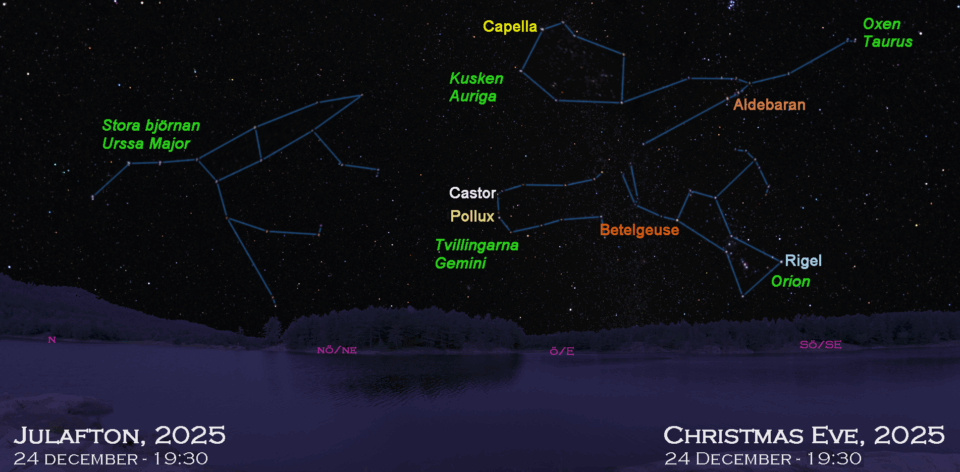

All of these bright stars belong to constellations, or imaginary figures that the ancients thought they saw. On this map they are shown as simple stick figures, with lines connecting the stars belonging to each one. Most people find this a better way to find them than trying to imagine their classical characters.

Note that we’ve also added Ursa Major, the Big Bear, in the north, and she(!) has been included here since it’s such a familiar constellation to most people. Brothers Pollux and Castor are in Gemini, the Twins, which is fitting for two stars appearing to have about the same brightness. Just above them is Auriga, the Charioteer, whose pentagon-shaped group looks like the front of a chariot coming directly at you from out of the sky. To the right of this is an obvious V-shaped group of stars, marking the face of Taurus, the Bull, with Aldebaran being one of his eyes. Continuing back down toward the southeast horizon, we find a very large constellation; Orion, the Hunter, with his belt of three stars in a straight row. Betelgeuse sits on his right shoulder, and Rigel at his left ankle.

Replacing the stick figures with the constellations the ancients thought they were supposed to look like, you can see why it’s easier to find your way around the night sky with the former rather than these. But you can see, for example, how close those such as Ursa Major, and Orion, resemble those characters from ancient stories about the night sky. Some of these stories were used to help our ancestors explain what they saw. Orion is fighting against Taurus, and has his club raised as if to hit the charging bull. Perhaps this helps explain why Taurus’ right eye, Aldebaran, is red because he got punched there.

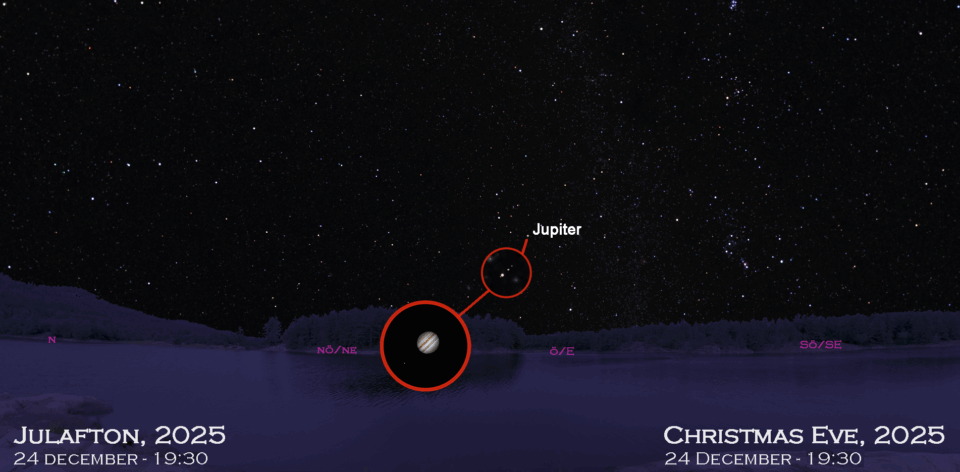

Focusing on what else can be seen at 19:30 on Christmas Eve, there is only one planet to observe. Jupiter is whitish-yellow in color and will be brighter than the stars of Gemini around it. You’ll know you’ve found Jupiter because, when compared to them, it’s not twinkling, but shines with a steady light. If you have a pair of binoculars, take a look at this, the largest planet in our solar system. If you hold them really steady—try leaning against a door frame, or on the roof of a car while standing very still—you might be able to make out what appear to be small stars in line with Jupiter’s equator. These are the planet’s largest moons as shown in the smaller circled picture. At around 19:30, you may be able to see three of the four, which were first discovered by Galileo Galilei using a homemade telescope in 1610. The larger circle shows Jupiter as it might look through an amateur telescope with higher magnification than binoculars, and includes one of those four moons, seen as the little “star” to the planet’s left.

Last, but certainly not least, there are some other interesting objects you can see naked eye, and can also observe with the same binoculars you turned on Jupiter. While seeing that planet’s moons might have been hard, these are very easy to spot and are worth a look.

Pleiades star cluster – starting in Taurus we can find this little cluster of stars, which looks like a tiny Big Dipper whether you look at it naked eye or through binoculars (represented by the red circle). According to ancient mythology, this group is riding on Taurus’s back. Located at a distance of about 444 light-years, its 1,000 confirmed member stars are thought to have formed out of the same nebula of gas and dust some 100 million years ago. When the Pleiades were born, there were still dinosaurs walking the Earth! Take a good naked eye look at the Pleiades and see how many stars you can count. Most people will see six, but under exceptional night sky conditions and if you have good eyesight, you might actually see seven, which leads to this cluster also being known as the “Seven Sisters.”

Hyades star cluster – this V-shaped group is another star cluster, and at its distance of “only” 153 light-years, it’s the closest such object of this type to us. If it were nearly three times farther away, it would look small and compact like the Pleiades. Even though reddish Aldebaran appears among the stars of the Hyades, it’s not a part of the cluster because it’s 65 light-years distant, and only appears to do so as it’s a foreground object along the same line of sight. The binocular view inside the red circle for the cluster shows this false association. Estimated to be 625 million years old, the Hyades are thought to contain between 500 and 1,000 stars, though most of them are not naked eye objects.

Orion Nebula – seen as a faint little ball of light hanging from Orion’s belt of three stars, this is one of the most famous examples of a nebula as seen in the northern hemisphere. We know that there are stars actively forming inside of it, which will one day be part of a newly-formed star cluster similar to the Pleiades and the Hyades. While it doesn’t look like much when seen naked eye or through binoculars (inside the red ring, which also includes the three belt stars making a diagonal line), that part we can see will eventually form something like 10,000 stars similar to our own Sun. And that’s not all as there is quite a large amount of gas and dust in the area which is not caused to glow to visibility by the hot young stars as are forming inside the Orion Nebula. At its distance of 1,344 light-years, this is the closest massive star-forming region to Earth.

Here’s hoping from ESERO Sweden that everyone has a happy and healthy holiday season, and we’ll see you again next year with more space and astronomy news.

Download the images

If you want to print the images to use when looking at the night sky, you can download a PDF with all the images from the article here.

By: Tom Callen