Fly me to the Moon…in February?

NASA plans first manned return to our nearest neighbor as early as next month

Not to date myself, but the last manned lunar mission to Earth’s only natural satellite was Apollo 17 in December 1972; the same year I graduated from high school. Most people don’t know there were three other Moon landing missions planned—Apollos 18, 19, and 20—but Republican party President Richard Nixon cancelled them. This was because of the continuing costs of the Vietnam War, and the fact that the Moon program had been started by Democrat President John F. Kennedy’s administration. Instead, NASA, under the Nixon administration, initiated the Space Transportation System (STS, better known as the Space Shuttles), which he saw a part of his future legacy.

Any mission into space with people on board has its share of risks, and all space agencies, regardless of country, try to make them as safe as possible. This also holds true when it comes to the test phase of any new spacecraft.

The previous mission, Artemis I, and the first flight involving NASA’s latest manned spacecraft was a crewless mission to the Moon and back again. Without any humans on board, everything was operated by commands from Mission Control on the ground. Launched on 16 November 2022, it completed a flyby of our nearest neighbor on 21 November, altered course, and then had a second one, 5 December, before returning back to Earth again.

It was important Artemis I met its goals of the first flight of the Orion Crew Module space capsule (CM), the ESA-built European Service Module (ESM) and its rocket, the Space Launch System (SLS). Not only did the spacecraft hardware have to function, like the capsule’s heatshield protecting it from high temperatures during reentry through our atmosphere, but so did the ground control systems overseeing the mission.

Here we can see, Integrity, the cone-like Orion Crew Module for the next Artemis mission sitting on top of the cylindrical European Service Module. Taken in March 2025, two of its four long solar panel arrays used to help provide electricity (the dark squares) can be seen folded against side of the ESM.

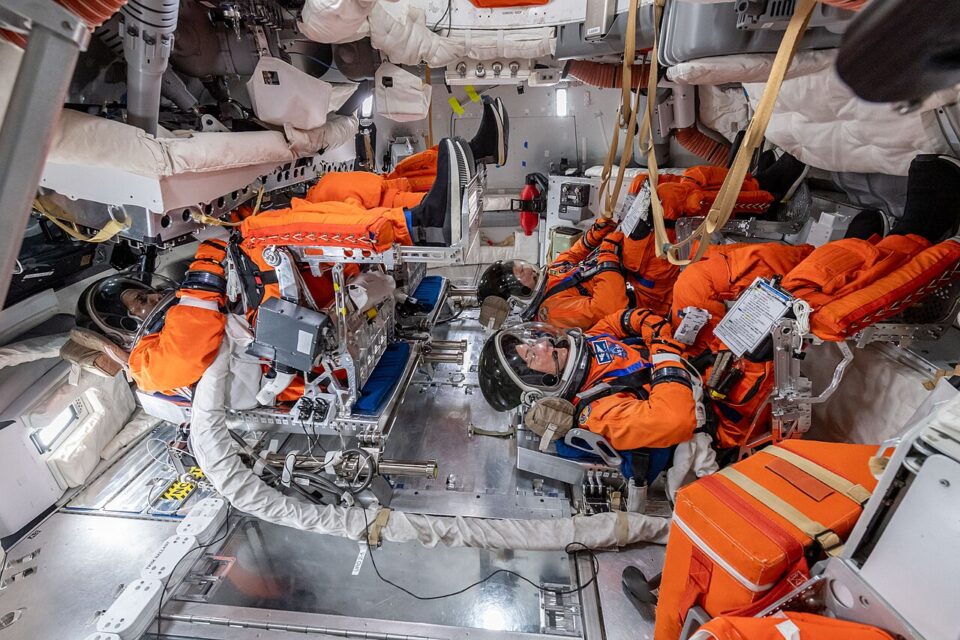

The four members of the Artemis II crew in this photo are training inside a replica of their Orion Crew Module. If you’re familiar with the interior of the Apollo Command Module from the Moon landings of the late-1960s and early-70s, this looks quite spacious by comparison.

Now it’s time for a full-up, crewed mission to place this spacecraft into lunar orbit as part of NASA’s plan to return to the Moon. And this is where present practice differs from the past, specifically the Apollo lunar landing program.

Before the manned Apollo 7 mission to test the Command Module and its supporting Service Module (known together as the CSM) in Earth orbit for two weeks, there were extensive unmanned tests. These included actual flights into space (Apollos 4 and 6), plus those made on Earth inside giant vacuum chambers as well as in large underwater tanks.

Since the CSM performed well in these trials, the next step was for Apollo 8 to test the Lunar Module (LM) in Earth orbit before the final “dress rehearsal,” and later the first attempt to land on the Moon. There was, however, a problem. The LM’s development was way behind schedule, and would not be ready in time. Which is what led to NASA deciding to send Apollo 8’s CSM and crew of three to orbit the Moon and return in December 1968. This could test long-distance operations as well as the spacecraft’s navigation computer there and back again, while allowing the delayed LM to be completed for testing during Apollo 9.

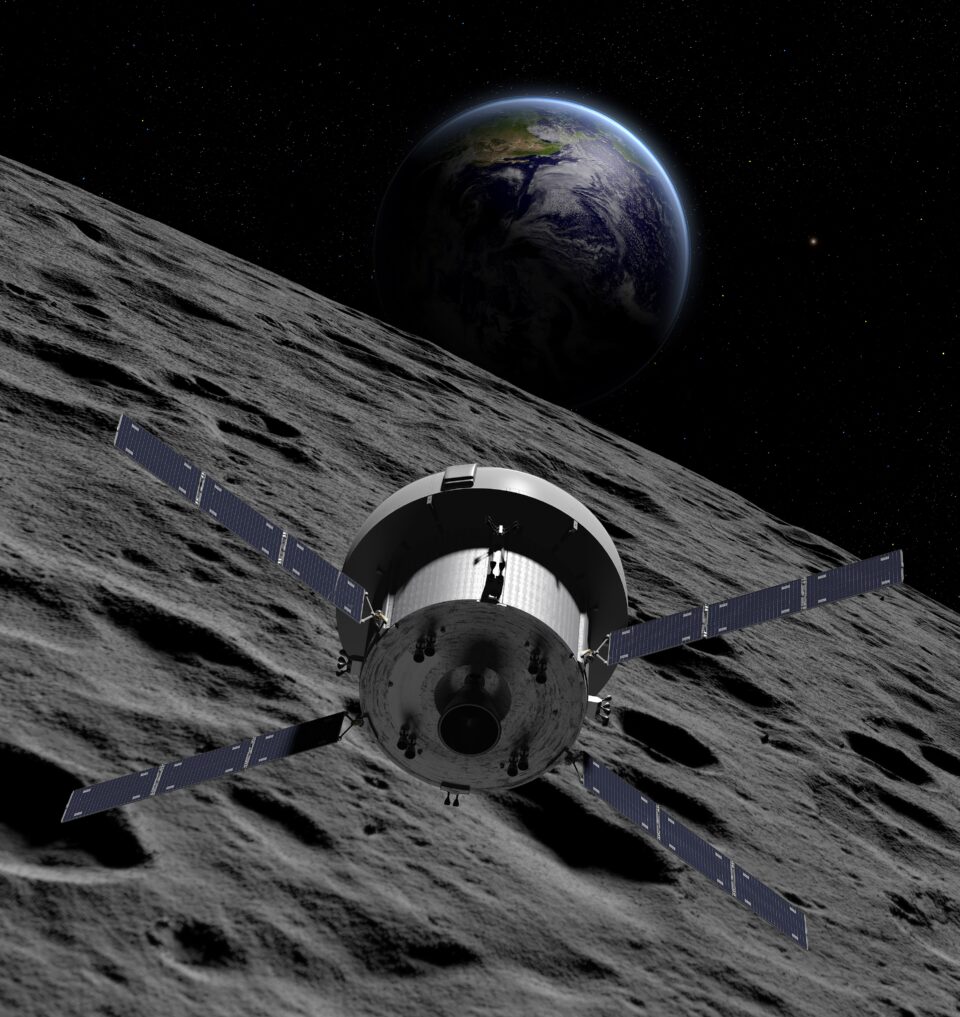

This artist’s impression shows what it might be like when Artemis II is in orbit around the Moon. Note the four extended solar panels sticking out to the sides, and our own distant planet Earth above the lunar horizon.

Artemis II, which could launch as early as this February, is going to attempt to pull off the Apollo 8 mission to the Moon with an untested spacecraft in that it’s never carried a crew onboard. As you could imagine, this carries some risks. There could be problems stemming from lack of flight experience with a completely new spacecraft never put in such a situation before. One of the reasons the three-astronaut crew of Apollo 13, which experienced an explosion on its way to the Moon in April 1971, came safely back to Earth again was because the Apollo CSM and LM (Lunar Module) were so well-understood by ground controllers.

Unlike the Apollo missions to the Moon starting almost 60 years ago with their three astronauts, there will be four onboard Artemis II. Seen here clockwise are Americans Christina Koch, Victor Glover (pilot), Canadian Jeremy Hansen, and American Reid Wiseman (commander).

In an effort to make people aware of the Artemis II mission, NASA has made a website where the public can get a digital souvenir “boarding pass” for the flight to the Moon. Potentially a fun project for you and your class, you need to enter your name online before 21 January 2026. It will then be stored on an SD digital memory card onboard the Orion Crew Module when it flies around the Moon. This same website produces the ”boarding pass” image for downloading, and features the name or text entered by the website visitor.

Personally, I find these upcoming return missions to the Moon interesting. I was 14 years old when Apollo 11 Neil Armstrong took those first steps from the Lunar Module’s ladder at the Sea of Tranquility on 21 July 1969(as seen in Europe). I watched it happening in real time with my parents, younger brother and maternal grandparents. After a gap of almost six decades, it would really be quite something to once again see someone set foot on lunar soil.

For more general information about Artemis II’s upcoming mission, follow this link.

By: Tom Callen